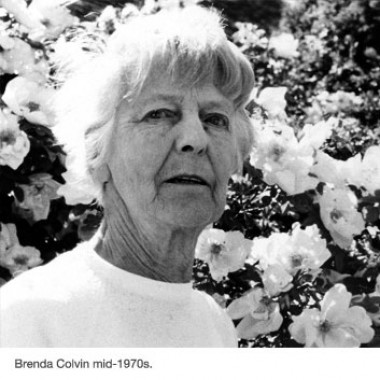

The late Brenda Colvin was a daughter of British India. The beauty of Kashmir and the flowers on its riverbanks remained vivid childhood memories. She attended Swanley Horticultural College where, inspired by Madeline Agar, she became passionate about landscape design.

She founded the practice in 1922 and by 1939 the majority of her 296 commissions were for private gardens. She was favoured for her brilliant plantsmanship, practical designs and sensitivity to the surrounding landscape. This included existing trees and plants – trees, she believed, “define and separate the open spaces, thus serving as do the walls and pillars of a building”.

The publication of her influential book Land and Landscape (1948), based on her wartime lectures and drafted whilst performing the courageous, but tedious duty of Fire Guard during and after the Blitz, marked a sharp shift from private gardens to urban and industrial landscapes. It was in transforming landscapes for power stations, reservoirs, industrial sites, new towns, national parks, new universities, hospitals, factories and mineral workings that Brenda made her post-war reputation. Always innovative, always with ecology and conservation in mind, she masterminded a great many original solutions. At Aldershot Military Town, for instance, she created new woodlands by naturally regenerating native species, and constructed a lake by excavating gravel to cover urban rubbish. At Eggborough Power Station, she framed the huge buildings in long shelter belts on raised banks, within which, near the cooling towers she placed recreation landscapes for the power station staff.

Her passion for landscape architecture reached far beyond the projects she worked on. In 1929 she co-founded the Institute of Landscape Architects (now The Landscape Institute). She fought hard to raise the profile of the profession, including the engagement of landscape architects at the start of the planning process, not “as an ornament to architecture and engineering”. Gale Common Hill is a good example of the way she worked. The site was being constructed using ash from nearby power stations, a money saving measure by the regional office of the Central Electricity Generating Board. When relieved of the consultancy for the Hill, after a month or two, she wrote to the director of the Board pointing out that she had not yet had the opportunity to hand over to the landscape architect succeeding her, who of course did not exist. She was reappointed forthwith and creating the landscape of this hill remained with the practice for thirty more years. In 1951 she was elected president of the Institute of Landscape Architects, the first woman to be president of any British environmental profession. Her CBE in 1973 acknowledged her great contribution to the profession and she continued to practice as a Landscape Architect until her death in 1981.